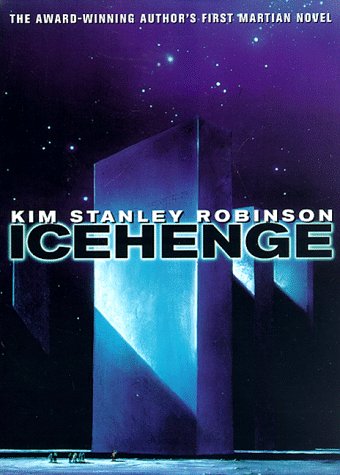

Icehenge

Icehenge is Kim Stanley Robinson's second novel, published in the same year as The Wild Shore, 1984. The novel consists of three stories connected through time, two of which were published before and significantly revised for the novel, and one written for the novel.

Icehenge deals with many themes, with each part complementing or shedding light to the other. In a background setting of the colonization of the solar system and social unrest in Mars, Icehenge explores the effects of longevity on human memory, historical memory, historical revisionism and the imperfect knowledge of past events. It shifts from a failed Martian revolution in 2248 to an expedition investigating these events, to an expedition to explore Icehenge, a mysterious monument on the north pole of Pluto, which is perhaps linked to a reclusive and wealthy woman who may hold the key to solving a mystery spanning centuries.

Structure

The novel consists of three parts bearing the names of the narrators and the date of the events, each written in first person narration:

- Emma Weil, 2248 A.D. : Written as a personal log or memoir.

- Hjalmar Nederland, 2547 A.D. : An important parallel is the ragged surface features of Mars and the half-erased memories of the narrator.

- Edmond Doya, 2610 A.D. : Switching between the Pluto expedition in the 'present' to Doya's past across the Solar System.

Synopsis

Part One: Emma Weil, 2248 A.D.

This part takes place in the asteroid belt, used by big mining companies, and on Mars, which is controlled by a Mars Development Committee; these essentially American and Soviet colonies serve to supply Earth with ore. Social unrest and emerging revolutionary groups, such as the Mars Starship Association (MSA) and the Washington-Lenin Alliance (WLA), threaten to overthrow the Committee.

Emma Weil, a Biological Life Support Systems expert, finds herself amidst an MSA mutiny aboard the Rust Eagle in the asteroid belt: it had been planned for her to take that ship, as the MSA wanted her to work with them, due to her past liaison with a leading figure of the MSA, Oleg Davydov. The ship is joined by two others: Emma is asked to help them with the life support systems, as the MSA plans to convert them into a starship with 80 years’ autonomy. Emma assists but does not join them. She goes to New Houston, Mars, where she is welcomed by the Texas cell of the WLA, and joins the rebellion against the Committee. A guerilla with Committee forces ensues and she escapes to underground.

Part Two: Hjalmar Nederland – 2547 A.D.

Mars is greatly populated and partly terraformed, and is a American & Soviet colony fully under the control of the Committee, which revises history to arrange each new discovery from the past. The WLA revolution of 2248 is known as “the Unrest” and the WLA is considered to have never existed. People have gerontological treatments that extend their life spans, but do not prevent memory loss.

Thanks to his Committee contact (and relationship), Alexander “Shrike” Selkirk, Hjalmar Nederland and a team of areologists (Mars archeologists) arrive at the ruins of New Houston and carefully start a dig, trying to build a case with concrete proof. They discover a buried field car that the rioters had used to escape, full of documents, names, plans, and Emma Weil's journal! A Committee press conference presents their finds: WLA should be seen as heroes for things that are now taken for granted.

The Persephone expedition discovers Icehenge on Pluto. After a year at the dig, Nederland goes back to Burroughs and publishes a theory about Icehenge being built by MSA. In Alexandria, he researches the archives and asks to get access to classified documents. He finds evidence of Oleg Davydov, the disappearance of two space ships and confirms the existence of the MSA; he publishes throughout. Shrike saves him from his exhaustion and memory losses; Shrike is promoted and Nederland thinks that the Committe is counting on their amnesia not to care that they're re-writing history.

A year later, Nederland is back at the New Houston dig. He goes on a long expedition through Martian terrain alone, to find out what some dots on a WLA map were. He has to go on foot with a cart and limited oxygen. He thinks he sees Emma and follows her to a lookout spot, loses her, ends up spending a night in exposure and hiking back with nearly no oxygen: he wonders whether he had a hallucination. He returns back safe with a resolve to keep pressuring to make Mars free. He will head an expedition to dedicate Icehenge to those killed in the Unrest, for the 350th anniversary of the convening of the Committee.

Part Three: Edmond Doya – 2610 A.D.

The Solar System is colonized and people often move from colony to colony throughout their lives. The Waystation, a hollowed-out asteroid, taxis between planets; it is owned by Caroline Holmes, a shipping magnate with a low public profile.

Edmond Doya (incidentally, Nederland's great-grand-son) spent his childhood with his father on the Jupiter moons, reading all of Nederland’s works and writing a book on Davydov. He moved to Titan alone, doing manual jobs, discussing philosophy at his boarding house and becoming a self-made scholar on Martian history, getting published and getting annoyed at Nederland's attitude. He had a life-changing experience when drunk on New Year’s Eve he came across an old stranger that said very convincingly that he built Icehenge.

He lived on the Waystation for 15 years, setting out to find out the truth about Icehenge, tracking down records from across the Solar System, painstakingly making connections and seeing patterns, doubting findings from other experts, saying the New Houston findings were planted. He eventually becomes a lecturer at the Waysation Institute for Higher Learning (founded by Holmes). He develops the Caroline Holmes theory: born on 2248, she would have built Icehenge with her own ships.

He is invited by Holmes to her abode, Saturn Artificial Satellite Four, in polar orbit around Saturn. They have lunch, visit the Sas's telescope observatory. He has a dream that she is accusing him of destroying Nederland’s work: was she somehow manipulating his dreams? He tells her everything about his search and she responds calmly that all evidence is circumstantial, and won't have him associate her with it. Edmond dares her to finance expedition. Later, he identifies and breaks into a large locked space: a perfectly realistic reconstruction of Icehenge on a smaller scale in a small planetarium, with laser beams that connect liths and prolong to stars. Edmond senses she had meant him to find the model and gets a feeling of already knowing her -- confusion with Emma?

Edmond joins the Snowflake expedition to Pluto; Nederland refuses. Edmond tiredly argues his academic position with other specialists onboard. One of them, Arthur Grosjean, a member of the original Persephone expedition, theorizes that Icehenge’s geometric design is based on ancient Celtic patterns; another, Theophilus Jones, has pulp theories about ancient astronauts.

On Pluto, they reach Icehenge. The Nederland expedition commemorative plaque on Pluto reads:

This Marker Has Been Placed Here

To Honor the Members of the

MARS STARSHIP ASSOCIATION

Who Built This Monument Soon After the Year

2248 A.D.

To Commemorate the Martian Revolution of 2248

And To Mark Their Departure From the Solar System.

There Will Never Come An End to the Good That They Have Done.

They study Icehenge for weeks. Through numerology and the megalithic yard, Jones discovers connections through the liths; the top of the tallest lith points to Pluto’s North Star and Edmond is reminded of the laser pointing upwards in Caroline’s model. They discover a hollow lith and descend through it: they find a cobalt blue ovoid chamber, with red streaks of changing patterns. Analysis and dating connects this to Holmes: “Doya’s Theory” is confirmed. Another theory states that the Perspehone crew built it before ‘discovering’ it. Jones makes a new theory: the Davydov expedition really happened and Emma’s journal is genuine; years later, Emma became Caroline; she visited Pluto, saw that the MSA had left no trace there, and built Icehenge; she wanted to slip the truth back into the world and fabricated evidence and planted it. Edmond and Jones wonder.

Background

The two previously published stories were:

- To Leave A Mark, first published in 1982 (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction 63); this became the first part of Icehenge. It is markedly influenced by the West/Soviet opposition still on-going at the time of writing and by Soviet revolution history; by extension it bears some similarities with the later Mars trilogy (social unrest on Mars and underground groups).

- On The North Pole Of Pluto, first published in 1980 (Orbit 18); this became the third part of Icehenge. Robinson gave the novella in rough form to Ursula K. Le Guin to read and edit while he was enrolled in her writing workshop at UCSD in the spring of 1977 (see KSR's entry in 80! Memories & Reflections on Ursula K. Le Guin). Views of Saturn from the space station inhabited by the Caroline Holmes were inspired by images of Saturn taken during the Voyager flybys (see KSR's introduction to Saturn: A New View).

This is completed by the middle part of Icehenge, which is the part that bears the most resemblance to the Mars trilogy: long passages with the exploration of the Mars terrain, sun mirrors to reflect sunlight, a Greek temple made of Martian rock (as in Red Mars, "The Crucible"), human longevity prolonged by advances in medicine and the effects of memory loss, tented cities often in craters (including one called Burroughs), even a character experiencing a sighting of a beloved person that is possibly a hallucination due to exposure. In this part, descriptions of the Martian terrain and areology are in italics; they are followed by thoughts and parallels with memory, the psyche, and the body marked with the passage of time.

Robinson was inspired for the structure of inter-linked short stories dealing with the uncertainty of memory and truth by Gene Wolfe's The Fifth Head of Cerberus.

Quotes

Part 1

"Something to leave a mark in the world, something to show we were here at all" - p.60

Part 2

"Memory is the weak link. This year I will be three hundred and ten years old, but most of my life is lost to me, buried in the years. I might as well be a creature of incarnations, moving from life to life, ignorant of my own past." - p.77

"What we feel most, we remember best." - p.78

"Life is the history of losses." - p.85

"You see, quiet people know they have a reputation for being close-mouthed. Sometimes the reputation is like a power, for they see their acquaintances think that when they are moved to speak it will be for something special. But that is also a sort of pressure, a pressure that grows as the years pass and the quiet person's reputation ages. What, after all, is really important enough to say? Not much. And quiet people become overly aware of that, and thus aware that most talk is a code masking vastly more complex meanings -- meanings unfathomable to the very people most aware of their existence." - p.85

"When human witness becomes weak evidence we're in bad trouble. I say it happened. I was here, I saw it. That's how we make history, by eyewitness accounts." - p.94

"And so history is made, because facts are not things. But things make facts or break them, or so the archaeologist believes. For every great lie of history -- if we assume they were all caught, which would be wrong -- for the Tudors' Richard III, for the first Soviet century, the Americans' Truman, the South African war, the Mercury disaster -- for each of these lies there had been a revision based on things." - p.100

"Now I begin to see that I have underestimated the memory. Events keep piling into it beyond its natural capacity, and it becomes packed tight. The chambers of the hippocampus and amygdala are overwhelmed. What remains of the distant past is jammed under the weight of subsequence, so that recollection is stressed, then disabled. But the memories remain. To be able to recall them takes a particular form of intelligence; so that when I curse my poor memory, I am really lamenting my stupidity. The other form of remembrance, the epiphanic recollection, is not really recollection at all. Under the right pressure the past bursts into consciousness, as a string of images we have created -- so we see not the past, but a part of ourselves, a sweet fragment to make us ache with the poignancy of time lost, and the beauty of connection with it. In the interregnum, in the naked moment between lives, we are most vulnerable to experience. On the Earth events have a sheer physical weight of significance. When we leave our natural span, and venture into the centuries, we are like climbers on Olympus Mons, hiking up out of the atmosphere. We must carry our air with us. I don't know what I am." - p.137

"The memory's the bone; imagination, flesh;

The animating spirit? -- is a forlorn wish." - p.149

"We could be making a Utopia of Mars, the planet insists we create a new society with every bloody icy dawn -- in fact we need to create such a society for our sanity's sake, because now we're all going to live a thousand years and we are going to have to live in the system we make, for year after year beyond our ability to imagine! That's what we've forgotten, Shrike. It used to be that people could say to themselves, why should I sacrifice my life for social change, it will take years and I'll not see the benefits of it, let this time be peaceful at least and the next generation can worry about it. That was one of the biggest forces against change, the selfishness of the individual who only wanted peace. But now people are dragging it out day to day on Mars forgetting that not their children but they are going to have to live in the future they build." - p.153

"Marx never guessed how technology would fix wood-and-steam capitalism into concrete for the ages. We're just tiny organic components of a solar-system-wide machine, Hjalmar. How can you fight it?" - p.154

"We plunge through the years like giants, as the poet said, and not one of us can be understood except as creatures continuously exfoliating. When memory fails to contain us we must love the past more than ever, to hold it to us -- or else the present becomes a meaningless blaze of color and sound, in which no two humans, great elongate beings, will be able to do more than touch at their very tips, their spatial selves -- no one will ever truly understand another. To love the past is to become fully human." - p.183

Part 3

"Could it really be true that all we knew was what our senses told us?" - p.198

"How can you be so sure, Edmond? How can you be sure?" - p.199

"Autobiography is now the necessary extension of memory. Five centuries from now I may live, but the I writing this will be nothing in his mind but a bare fact. I write this, then, for that stranger myself, so that he may know who he has been. I hope it will be enough. I am confident it will; my memory is strong." - Edmond, p.224

"Acute students of finance will have observed that money, abstract concept though it is, behaves as if it had mass. Economic laws imitate physical laws. Everyone's collection of money is a planetary body, in other words, exerting influence on everyone else's. Thus the more money you have the stronger its gravity is, and the easier it is to attract more. Now most of us own mere asteroids of money. But some people own stars of money" - p.233

" I considered it. "Do you really think that if we did not exist, Saturn would not be sublime?" I thought she wasn't going to answer. The silence stretched on, for a minute and more. Then: "Who would know it?" "So it is the knowing," I said. She nodded. "To know is sublime." " - p.247

"How I hate people who say that! Everyone is a political person, don't you understand that? You would have to be autistic or a hermit to be truly apolitical! People who say that are merely saying they support the status quo, which is a profoundly political stance--" - p.257

"There are so many influences in our lives that we don’t control – you might as well not worry about another one that you may be making up." - Theophilus Jones, p.266

"We dream, we wake on a cold hillside, we pursue the dream again. In the beginning was the dream, and the work of disenchantment never ends." - Theophilus Jones, p.287 (closing phrases)

Publication History

- Ace Books ISBN 0441358543, 1984

- Futura Orbit ISBN 0708881661, December 1985

- MacDonald ISBN 0356124029, October 1986

- Denoël ISBN 2207304256, as Les Menhirs De Glace, (French translation) September 1986

- Editrice Nord ISBN 8842901717, (Italian translation) 1986

- Bastei-Lübbe ISBN 3404240928, as Die Eisigen Säulen Des Pluto, (German translation) 1987

- Tor Books ISBN 0812502671, September 1990

- Voyager ISBN 0006482554, September 1997

- Zagrebačka naklada ISBN 9536234262, as Ledeni Hram, (Croatian translation) 1997

- Лира Принт ISBN 9548610183, as Айсхендж, (Bulgarian translation) 1997

- Tor Orb ISBN 0312866097, July 1998

- 漓江出版社 ISBN 7540726105, as 冰柱之谜, (Chinese translation) 2001

- Gallimard ISBN 2070313042, as Les Menhirs De Glace, (French translation) 2003

- Minotauro ISBN 8445074954, as Icehenge: La Memoria Perdida, (Spanish translation) March 2004

- Voyager ISBN 9780007336746, August 2009

Reviews

- Jo Walton - Tor.com

- Val's Random Comments

- Richard - Book Addiction

- From A Sci-Fi Standpoint

- Words Uttered in Haste

Resources

- Excerpt at Macmillan.com

- Icehenge at The Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Icehenge at Google Books

- Icehenge at Goodreads

- New Houston flag reconstruction at Flags Of The World

Comments

Icehenge

https://ynotlleb.wordpress.com/2012/04/01/the-first-novel-from-ksr/