The Martian Connection: John Carter of Mars

Submitted by Kimon

With Disney releasing the blockbuster film John Carter, based on Edgar Rice Burroughs' classic pulp series Barsoom/John Carter of Mars, there are several articles on Mars in fiction popping up. You can say what you like about the fact that the vision of Burroughs' Mars is now extremely dated (and you can say even more things for today's film still choosing Mars as the setting!), but it left an undeniable mark in the history of science fiction.

Inevitably given the Mars trilogy, Kim Stanley Robinson offered some thoughts on Mars for some of those articles.

For SF Signal:

The appeal of Mars is that it’s real. We can see it in the night sky, and we know it’s the next planet out. And now we know a great deal more about it than that. Its surface looks like parts of Earth, and has huge features, much bigger than equivalent features on Earth (volcanoes, canyons). It’s possible it still harbors bacterial life underground. It’s also possible we could visit it, and set up stations to inhabit and study it.

So: it’s real but empty, beautiful and remote, but within our reach, just barely. It’s this combination of qualities that gives it its appeal. We want to fill that emptiness with stories.

For Space.com:

"because of the Percival Lowell hallucinations, educated people from all over the planet from about 1895 to about 1935 could in good conscience believe there might be life on the next planet out, and maybe even intelligent life," said science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson, who has won Hugo, Locus and Nebula awards for his Mars trilogy ("Red Mars" in 1992, "Green Mars" in 1993 and "Blue Mars" in 1996) and is author of the forthcoming novel "2312."

The first major works to deal with Mars were Kurd Lasswitz's "Two Planets," an 1897 German novel that imagined a technological utopia on the Red Planet, and H.G. Wells' "War of the Worlds" (1898), in which Martians invade Earth.

"'Two Planets' had this powerful influence on the German Rocket Society and rocket pioneers such as Wernher von Braun — we might not have been able to reach the moon if weren't for this science fiction about Mars," Robinson said.

For the Los Angeles Times:

“Mars has this secret, sneaky, almost mystical pull on people’s imagination,” says Kim Stanley Robinson, the Central California science-fiction writer who’s penned several important Mars novels.

[...] “It was a zeitgeist thing,” says Robinson. “The whole science-fiction community said, ‘We have to get beyond the Lowell-Burroughs vision.’” And though a number of writers — Frederik Pohl, Philip K. Dick — rendered distinctive visions of the Red Planet, the first and most enduring was Ray Bradbury’s.

The magazine stories that were collected in “The Martian Chronicles” in 1950 were poetic and mythical and showed a planet with a graceful, tragic race on the verge of fading out, just as mankind is showing up. “As a kid he must have loved Burroughs,” says Robinson. “In ‘The Martian Chronicles,’ he realized that Martians would be ghosts inside our minds. By the ’40s, we knew there was no oxygen, almost no water…. He was saying, ‘They may be hallucinations, but they will still haunt us.’”

And these Martians, as Newitz points out, were truly alien — not even humanoid. “The Martians are unknowable. To live on Mars you will have to become a Martian.” This, and the stories’ flashes of environmentalism, showed thinking about colonial conquest maturing past the Manifest Destiny model, she says.

A little later, the dream died unambiguously. The Mariner 4 spacecraft flew by Mars in 1964 and sent back the first detailed photographs: No canals, no seas, no aliens. “This is actually a dead world,” says Newitz. “How do we cope with that? We thought these were people we could be friends with.”

It took until the ’90s for a fictional masterpiece to adjust to the idea. Robinson’s Mars trilogy — “Red Mars,” “Green Mars,” “Blue Mars” — looked at the slow process of terraforming a dry planet by an international team and kept a focus on what the planet did to the humans who transformed and settled it. The books, Newitz says, are about “the horror of meeting ourselves — all our bad qualities are transported there.”

But even after these visions of a civilization on a sister planet teeming with life died, the shimmer of Mars hasn’t entirely dimmed.

It may be hard to move forward: Robinson’s Mars trilogy will be a tough act to follow, and the writer himself has little interest in going back. “It’s a closing-down story space,” says Robinson, “compared to Earth and climate change, or Earth and overpopulation, and so on. Earth is gonna be intensely interesting. It’s also pretty clear with the space program’s budget that we’re going to be on this planet for a while.”

Following up on the film-and-Mars topic, Alyssa Rosenberg, who had moderated a Red Mars book club reading recently, wrote a piece on"Towards Smarter Politics In Art, As a Means to Better Art", which tackles the representation of politics in films through narrative, aesthetics and the power of images in such films as Avatar, Iron Man, The Triumph of the Will, The Ides of March, Primary Colors, and eventually tails into Robinson's Mars trilogy:

Like Avatar, Robinson’s Mars trilogy has its artistic flaws, particularly a tendency to lapse into overly technical prose that explains everything from the way time works on Mars to the composition of Martian soil. And like Avatar, the Mars trilogy’s novel and refreshing engagement with politics more than makes up for those lapses. Simply by asking us what we’d dare to make new if we freed ourselves from of our gravity and our political system, Robinson’s performing a valuable service, removing some of the heaviest constraints on our thinking about everything from corporate power to energy consumption to living in multi-faith communities. His characters experiment with a barter-based economy, integrate Islam and Buddhism, and learn what it means to live beyond the normal human life-span. We may never reorganize our society so dramatically, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth considering what we’d do with the knowledge and concepts that we have if we were given an opportunity to radically realign them. Fiction can suggest juxtapositions that may not occur to us. Scenarios that seem impossible now may suddenly become pressingly important. And as his characters experiment with everything from architecture to monogamy, Robinson manages to affirm that some essential principles of humanity will carry into the future with us, making the prospect of heading off towards it less frightening.

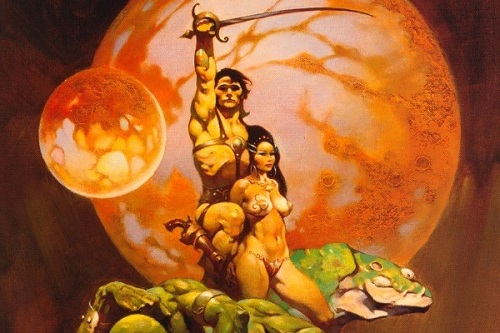

(Image: cover for the 1970 Doubleday edition of "A Princess of Mars" by Frank Frazetta)